This past weekend I had a chance to present some of the findings of my book, Good Behavior and Audacity to an audience of friends and arts educators. My ever-generous friend from the Music Center Education Division, Susan  Cambique Tracey (featured in an earlier post), and her husband Paul sponsor about four salons each year devoted to the arts and arts education, and they invited me to do one. It was wonderful fun. Susan says the salons are their way of giving back, showing gratitude for their life in arts education, and I felt that gratitude glowing around me all afternoon. The session was documented in film so I’m excited that I will be able to share bits of it in upcoming posts.

Cambique Tracey (featured in an earlier post), and her husband Paul sponsor about four salons each year devoted to the arts and arts education, and they invited me to do one. It was wonderful fun. Susan says the salons are their way of giving back, showing gratitude for their life in arts education, and I felt that gratitude glowing around me all afternoon. The session was documented in film so I’m excited that I will be able to share bits of it in upcoming posts.

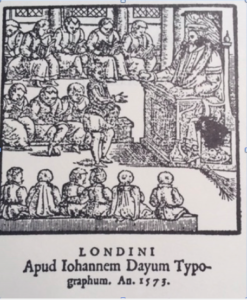

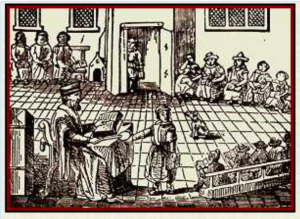

I started the program with a visual exploration of these four woodcuts picturing Elizabethan classrooms. The first two are dated 1573, the very year that William Shakespeare turned nine, so looking at them you may imagine him as one of the boys pictured.

One result of the Humanist movement in  early 16th century England was a robust interest in pedagogy, with many books written on the subject. One of the most famous of those teacher/authors was Richard Mulcaster, who just happened to train Thomas Jenkins and John Cotham, two of Shakespeare’s teachers at Stratford’s Latin grammar school. Reading his two books, Positions and Elementarie, was one of the igniting revelations that got me going on my own book, because of Mulcaster’s use of the arts in his daily instruction. The title of my book is actually taken from a quote by a 17th century jurist who had been a student at the Merchant Taylors’ School while Mulcaster was the headmaster. He credited Mulcaster with offering daily instruction in both vocal and instrumental music, accompanied by dance, and with using theatre to teach “good behavior and audacity.” Mulcaster also included drawing as one of the essential teachings for young children, so all of the arts were present in his school.

early 16th century England was a robust interest in pedagogy, with many books written on the subject. One of the most famous of those teacher/authors was Richard Mulcaster, who just happened to train Thomas Jenkins and John Cotham, two of Shakespeare’s teachers at Stratford’s Latin grammar school. Reading his two books, Positions and Elementarie, was one of the igniting revelations that got me going on my own book, because of Mulcaster’s use of the arts in his daily instruction. The title of my book is actually taken from a quote by a 17th century jurist who had been a student at the Merchant Taylors’ School while Mulcaster was the headmaster. He credited Mulcaster with offering daily instruction in both vocal and instrumental music, accompanied by dance, and with using theatre to teach “good behavior and audacity.” Mulcaster also included drawing as one of the essential teachings for young children, so all of the arts were present in his school.

So now, my readers, I would like to engage you in the same visual exploration and see if we can draw some conclusions about Elizabethan classrooms.

So now, my readers, I would like to engage you in the same visual exploration and see if we can draw some conclusions about Elizabethan classrooms.

Examine the four woodcuts closely and look for similarities and differences.

These images are all from the internet, and there isn’t much accompanying information about any of them, so I am in the same position as you are looking at them. What we see we see, and, using visual thinking strategies, what we conclude is what we conclude. I cannot verify our conclusions, but I do have the advantage of several years of research to draw upon and so I will add information where I can.

First of all, yes, indeed, that is a dog in two of the pictures. I have no explanation for the dog. (It does bring to mind the comic presence of a dog in both Two Gentlemen of Verona and A Midsummer Night’s Dream, but those were not classroom dogs!) Is the presence of a dog an indication that those two classrooms were rural? Perhaps.

Also, this last one is much busier than the others, and much more crowded (and there is no dog), so perhaps this one depicts a school in London?

Also, this last one is much busier than the others, and much more crowded (and there is no dog), so perhaps this one depicts a school in London?

Here are a few more observations:

1. In each one the headmaster appears to be holding a rather exalted position, in a throne-like chair. And he has a switch close by in case he needs it to maintain control. In fact, in this last one another adult (likely an usher, or assistant teacher), is flogging the naked bottom of a boy.

I’ve read that flogging was not uncommon. In fact there were plenty of euphemisms for it, like “marrying the schoolmaster’s daughter,” or “learning a new song today.” But most of the books on pedagogy from the time, including those by Mulcaster, explicitly state that kindness and reason were preferable to corporal punishment. I suspect that the mere presence of the switch may have been enough to keep order in most cases.

2. In the last picture we see that there is musical notation on the back wall and there appears to be a child playing a keyboard instrument like a virginal and other children singing. Most statutes from the time list regular music instruction, and at least at Merchant Taylors’ School it was included every day.

3. In each picture there is a child standing in front of the headmaster, and in the last one there are several in line waiting their turn. They are reciting their memorized lessons from the classics, and from what I’ve learned about physical rhetoric, or “rhetorical dance,” they were required to do so with appropriate gesture, expression, and emotion.

4. The other children in the room are engaged in their own activities—reading, writing, or talking to or perhaps collaborating with the students next to them. They are paying no heed to the child in front of the headmaster, an indication that there was nothing out of the ordinary about a student declaiming his lessons; it went on all day long and attracted no attention.

5. There are no desks. The children are reading from and writing in notebooks, or tables. Remember that Hamlet, in his frenzy after his encounter with his father’s ghost, says, “My tables! Meet it is I set it down, / That one may smile and smile and be a villain!” He is talking about exactly what these children are holding: their own tables, which accompanied them to and from school every day. In those tables they wrote down the lines they were required to memorize. They also wrote down rhetorical figures they found in their classical readings and kept them organized in columns. At some point, they also wrote down their own invented examples of figures, often developed in collaboration with their peers.

6. In the absence of desks, there is an open space in the center of the classroom. That open space was called a place to be heard: an auditorium. A stage!

So….setting aside the corporal punishment and the dog: focus on this thought: what does it mean for a child to go to a school where the core goal is to be seen and heard.

Hi Robin, JL’s report on the evening doubled the regrets I felt about missing the immersion in educational Shakespeare once again. Brava. I had mentioned the chapter on “Drama” by a noted medievalist of parliamentary institutions, Maud Cam (early 20th century). She would have joined me in applause: brava!

How fun to unpack those images. The stage. The performance in front of the head teacher. The variety of action in the background. Very theatrical–no wonder this nurtured young Will.

This is quite fascinating Robin. Shakespeare’s school reminds of a shaolin temple for the arts, training it’s students to use language and at it’s highest level upon graduation. The fact that the students were also taught to physicalize language is also quite interesting. Looking forward to your next post!

Heya i’m for the first time here. I came across this board and I find It truly useful & it helped me out a lot.

I hope to give something back and help others like you helped me.