The Blackfriars Theatre

If Charles William Wallace, in The Evolution of the English Drama up to Shakespeare, is to be believed, it was at Blackfriars Theatre, in the early 1580s, that the Golden Age of Elizabethan Theatre was launched. He makes a convincing argument which I will attempt to summarize here. It is perhaps an implausible leap to say that without the boys’ companies there would have been no Shakespeare, but let’s look at the evidence.

The wildly popular flourishing in the 16th century of the Children of the Chapel and, later, the Children of St. Paul’s and the Children of Windsor, had a lot to do with the youth of three monarchs. Youth craves entertainment, often the edgier the better, and Henry VIII, his son, Edward VI, and his daughter Elizabeth were all very young when they first ascended the thrown. All three of them loved the antics of the theatrical, satirical and often histrionic productions of the boys’ companies.

In my previous post I gave a glimpse into the court of the young Henry the VIII and listed some of the dozens and dozens of titles of interludes and plays performed at court by the Children of the Chapel. As Henry aged and his reign was fraught with religious and political turmoil, his own interest in the plays may have waned, but apparently that of his court did not. As I said in the last post, there are still hundreds of records detailing the titles and the costs associated with costumes, sets, and generous payments to the playwrights of the plays presented by children; but the scripts attached to all those titles no longer exist. We know that they sometimes caused offense and sometimes elicited rave reviews, but, sadly, we don’t know exactly what came out of the mouths of the boy actors. That began to change during the reigns of Edward VI and his sister Mary.

The Lord of Misrule

Edward was only king for six years, and died when he was fifteen, so he himself did not have much of a chance to influence this history. Apparently he was fond of the tradition of the Lord of Misrule, which was a chaotic and riotously funny entertainment common during Christmas festivities, in which a person of low standing, a peasant, was made king for a spell, the court was turned upside down, and all the rules were broken. It may have been something like today’s mardi gras festivities. The boy king would not have a chance to outgrow his childish taste for buffoonery, but he did put the former headmaster of Eton, Nicholas Udall, in charge of his entertainment, and despite his protestant leanings, Udall continued for awhile in the court of the pious Catholic sister Mary.

It was in the first year of Mary’s reign that the first surviving script for a boys’ company was performed. Freely adapted from Miles Gloriosus, by Plautus, Udall’s play Ralph Roister Doister was such a huge hit that it was published and reenacted many times. This was the first script written for boys that we can still read today. There were many, many more to follow!

But it was under Elizabeth that the boys’ companies really came into their own, and it was at Blackfriars Theatre that their popularity flared up so brightly and dangerously that it had to be extinguished for a time.

The young Elizabeth of the 1560s did not yet have available the outstanding men’s companies that formed in the succeeding generation, and she had an abiding love for performances by boys. The Children of the Chapel had been allowed to go somewhat fallow under Queen Mary, but when Elizabeth became queen she recruited an old friend, Sabastian Westcote, to take over the mastership of the Children of St. Paul’s, which was a long standing choir only loosely associated with the grammar school. Almost immediately they began performing plays at court. Later Elizabeth also sponsored the Children of Windsor to be available when she was visiting there.

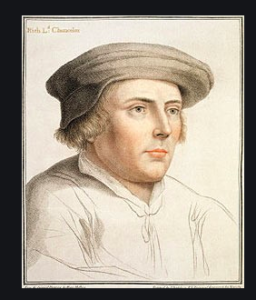

Richard Edwards, Playwright

Then in 1561 the master of the Children of the Chapel died, and she was able to hire the finest dramatist of the time, Richard Edwards. Ever heard of Richard Edwards? No?! Well, let me tell you! He was said by Barnaby Googe to be the greatest poet who had ever written in the English language or who ever would: “Far surpassing Plautus and Terence and not likely to be equaled by any poet in the future!” Poor fellow. Just his luck soon to be equaled, and left in the dust, by Shakespeare and company!

The new Queen Elizabeth also favored the theatricals of Latin grammar schools in London. The students of Richard Mulcaster, the headmaster of the Merchant Taylors’ School, were frequently invited to perform at court, as were students from Eton and Westminster. The great men’s companies were still decades away from their ascent, but there were three vibrant boys’ companies and several troupes of scholars always ready to perform. Indeed, between the children’s companies and the grammar school students, theatre in the first thirty years of Elizabeth’s reign was entirely dominated by boy actors.

Two crucial events occurred almost simultaneously in late 1570s. When Elizabeth first came onto the throne, theatre, performed by both men and boys, was liberated from Queen Mary’s moralizing expectations, and a lively new era of drama was born. During the first years of her reign, the private theatre of the court spun off on into countless motley but popular public ventures. In time, inevitably, public theatres became profitable, and men’s companies began sprouting up all over the country. In London, the situation got so noisy and chaotic that there was an outcry by some of the more puritanical elements of the population, so in 1572 Elizabeth issued a restrictive statute that allowed performances only by companies under noble patronage. This turned many adult players outside of the city into vagabonds and beggars, but in London, ironically, it eventually lead to the establishment of the first two permanent playhouses, Burbage’s Theatre and the Blackfriars.

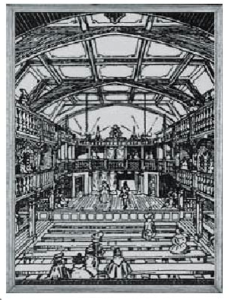

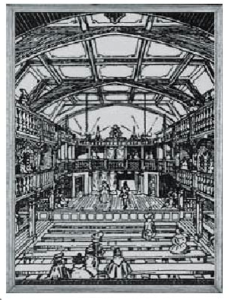

Noble patronage had a crucial function. The court needed their favorite companies to be available at all times. This meant they had to have a place to rehearse. In 1576 Richard Farrant, then the master of the Children of Windsor, leased a section of an old, abandoned monastery that had belonged to the Dominican’s before Henry VIII turned them out. They were known as the black friars because of the color of their robes, and their monastery was called Blackfriars. There Farrant proposed to train his own boys and invited William Hunnis, Edwards’ successor as master of Children of the Chapel, to join him. Together they prepared their young players for their court appearances, gaining some financial advantage by charging admission to the public for their “rehearsals.” Their first play, The History of Mutius Scevola, was performed at Blackfriars and then at court for the following Twelfth Night in 1577. They continued this productive relationship with the court for the next six years.

Also in 1576, the very same year, James Burbage (theatre impresario and father of the famed actor Richard) opened the Theatre, to house his company, the Lord Leicester’s Men. This was the first permanent home for the burgeoning industry developing around men’s companies, and it made all the difference. Before 1573 there were almost no performances at court by men. After the Queen’s restrictions that empowered the men’s companies that had noble patronage, they became a constant, and no year passed without at least one play, then more and more. The race for the Queen’s favor between the men and the boys was on. As we know, by the time Shakespeare arrived on the scene, the race was over and the men had won, but for several years the boys at Blackfriars gave them spirited competition.

Edward de Vere, Earl of Oxford

Farrant died in 1580 and three years of legal squabbles followed, with Farrant’s widow and William Hunnis trying to keep the venture alive. The landlord of Blackfriars was dismayed by amount of traffic caused by the large audiences coming and going to the so-called “rehearsals,” and he was desperately trying to cancel the lease. To the rescue came Edward de Vere, the Earl of Oxford. Remember him?—the very man who is today credited by some with the writing of Shakespeare’s plays? Wallace describes him as a noted “swaggerer, roisterer, brawler, coxcomb, musician, poet,” but with his noble title he was able to hold the landlord at bay and take over the lease of Blackfriars.

Oxford was also a noted patron of the arts, and the children performing at Blackfriars became known, briefly, as Oxford’s boys. He brought along his favorite playwrights, the scathingly witty young men, John Lyly and George Peele. Together they set about turning their new real estate into a profitable venue that could compete with the newly popular public theatres. It was private only in the sense that it was indoors, and more expensive than the Curtain, the Fortune, or Burbage’s Theatre, all of which by now housed men’s companies. The new impresarios still received patronage from the court, but in addition they increased the number and price of performances for the more well-to-do public. Not surprisingly, that public ate it up.

John Lyly, Playwright

Their collaboration at Blackfriars was a brief flare, lasting little more than a year. In 1584 the landlord finally succeeded in a long-fought quest to revoke the lease of the rowdy band of children, and for the next fifteen years Blackfriars was silent. But a new style had been launched and continued to thrive. John Lyly wrote at least eight plays presented at court by the boys, including Compaspe, Sapho and Phao, Endymion: The Man in the Moon, Gallathea, Midas, and Love’s Metamorphosis. Of these, apparently only the first two and George Peele’s The Arraignment of Paris were offered first to audiences at Blackfriars, but the plays continued. After Blackfriars went dark, Peele returned to the public theatre, but Lyly continued to write for the boys at St. Paul’s, using their traditional venue attached to the Cathedral. Several more of his plays were presented at court, and audiences continued to enjoy them. Other playwrights got into the action too. Robert Greene contributed A Looking Glass for London and England, Orlando Furioso, and The Scottish History of James the Fourth. The public could not get enough of the brisk and lively dialogue, the gossipy allusions to public figures, and the poking of fun at topical issues. For a short but history-making moment, Oxford’s Boys, first formed at Blackfriars, were the hottest ticket in London.

According to Wallace, it was at Blackfriars that the highly stylized aesthetic of the court merged with that of the earthier, native theatre that had been growing in popularity, and this merging launched a hybrid: the clamorous, riotous, and exuberant age of Elizabethan drama. Native English drama had been narrating its own, parallel history for decades, beyond the purview of the court but reflecting its passions. Short, farcical amusements, not unlike Italian commedia dell ‘arte, had been performed for popular audiences in English, in streets, inn-yards, and town squares for many decades. These shows were probably hilarious, but they were essentially formless. Most of them were improvised, and we have very few actual scripts on which to base a study; but with a new fascination with our language came translations of the great Latin plays, and gradually classical structure was adapted into home-grown theatre.

As the boys’ companies grew in popularity, there was a constant need for material, and enterprising playwrights ransacked Plautus, Terence, Menander, and Seneca for material, writing plays that were squarely based in London but based on classical models. Stylistically, what distinguished these dramas from those performed at court was the lack of the expensive adornment required by the masques. Without the dazzling spectacle, they had to rely on good stories and clever dialogue to maintain the interest of the audience. Wallace sees a direct line of evolution from the children’s companies to the magnificent era of Elizabethan drama. The early plays at Blackfriars created the template, and he believes that it was there that the court collided with the street and a new dramatic genie was unleashed. He cites 1584 as the pivotal year that everything changed. Lyly and Peele took over for Farrant and Hunnis and found the courtly theatre as it was, with song and dance and masques and pretty dialogue. They just chopped it into five acts and gave it space to include the tropes of native English theatre. They added thunder, fencing, battles, blood, buffoonery, and constant, rapid action and voila! Shakespeare!

Ironically, it was the huge success of the Blackfriars Theatre that led to its demise. The nightly disturbances caused by rowdy playgoers traveling to and from the theatre finally got too much, and the landlord cancelled the lease in 1584.

But audiences were becoming more and more sophisticated and they loved the spicy, edgy satire that was Lyly’s forte. He continued to write for the Children of St. Paul’s and he got himself into a world of trouble doing it. As has always been the case, politics and satire are Siamese twins that cannot be separated, and the more the bite of satire, the more dangerous it is. In 1589 there is a record of the Children of Paul’s being “put down” after John Lyly got them tangled up in a political kerfuffle between the state and a group of anti-episcopal Puritans. It was called the Marprelate controversy. Someone, or a group of persons, all going by the name of Martin Marprelate, began publishing pamphlets that attacked the Church of England and individual priests. They were so persistent and so contentious that the court asked their wittiest playwrights, Lyly among them, to help them respond. We don’t have the play that Lyly wrote for them and that the boys performed. It was certainly written on the side of the state—Lyly was no fan of the Puritans—but apparently it was a double-edged attack and insults were flung freely in all directions. The over-stepping must have been very grave because the reaction to it was severe. In the following months the government issued a strict decree that no play could be performed without first being approved by a state censor. The boys ceased playing at court almost completely, and Lyly’s career was over.

The boys’ companies mostly went dark for the first decade of the Golden Age of Elizabethan drama, but they had one more dazzling flowering in the Jacobean era which will be the subject of one more post: The Little Eyases.

“No one knows when boy singers were added to the Chapel Royal or other church choirs, but they were probably present from the very beginning, their treble voices being thought to be the closest to the voices of angels. There was a religious pursuit of this purity of tone. Churches, abbeys and cathedrals were designed acoustically to capture it: massive sound boxes that amplified these “fairest voices.” Choir schools, attached to churches and training children for church choirs, played a role in the pre-reformation history of British education. They offered free education to able students. Their purpose was to assure a sufficient number of well-trained voices to supply the needs of the church. As we shall see, Erasmus himself attended a song school in Utrecht, perhaps because it was an opportunity for a free education. The earliest choirmasters were usually almoners, the men who distributed alms to the needy.

“No one knows when boy singers were added to the Chapel Royal or other church choirs, but they were probably present from the very beginning, their treble voices being thought to be the closest to the voices of angels. There was a religious pursuit of this purity of tone. Churches, abbeys and cathedrals were designed acoustically to capture it: massive sound boxes that amplified these “fairest voices.” Choir schools, attached to churches and training children for church choirs, played a role in the pre-reformation history of British education. They offered free education to able students. Their purpose was to assure a sufficient number of well-trained voices to supply the needs of the church. As we shall see, Erasmus himself attended a song school in Utrecht, perhaps because it was an opportunity for a free education. The earliest choirmasters were usually almoners, the men who distributed alms to the needy. into service for the crown, and the Chapel Royal consistently had a small number of singers to complement the adult musicians. Their voices were, and are to this day, a thing of transcendent beauty. Boys’ voices broke later five hundred years ago than they do today, evidently because there was less protein in the diet. A boy who began his service in the Chapel at the age of seven or eight could continue to sing sweetly until the age of sixteen or seventeen, during which time he received an education overseen by the choirmaster.

into service for the crown, and the Chapel Royal consistently had a small number of singers to complement the adult musicians. Their voices were, and are to this day, a thing of transcendent beauty. Boys’ voices broke later five hundred years ago than they do today, evidently because there was less protein in the diet. A boy who began his service in the Chapel at the age of seven or eight could continue to sing sweetly until the age of sixteen or seventeen, during which time he received an education overseen by the choirmaster.

both parents is haunted by the lost opportunity to ask unanswered questions. I’m no different. Now that I am pursuing this history project I could kick myself for not filling in the snippets of information they shared casually over the years. That day, walking around the Village, we passed the

both parents is haunted by the lost opportunity to ask unanswered questions. I’m no different. Now that I am pursuing this history project I could kick myself for not filling in the snippets of information they shared casually over the years. That day, walking around the Village, we passed the So I started searching the internet and found an article written in 1986 by Margaret E. Berry, Former Executive Director of the National Federation of Settlements and Neighborhood Centers. There I was astonished to learn how many progressive movements that we now take for granted had their roots in the settlement houses: The kindergarten (child garden) movement, federal fair housing legislation, legal aid services, meals on wheels for the elderly, even Roosevelt’s New Deal and the Works Projects Administration! But what struck me most were the philosophical underpinnings of their arts and cultural activities programs.

So I started searching the internet and found an article written in 1986 by Margaret E. Berry, Former Executive Director of the National Federation of Settlements and Neighborhood Centers. There I was astonished to learn how many progressive movements that we now take for granted had their roots in the settlement houses: The kindergarten (child garden) movement, federal fair housing legislation, legal aid services, meals on wheels for the elderly, even Roosevelt’s New Deal and the Works Projects Administration! But what struck me most were the philosophical underpinnings of their arts and cultural activities programs.

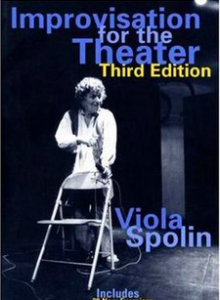

the Recreational Training School there. The school taught a one-year educational program to teachers, in group games, gymnastics, dancing, play theory, social problems, and dramatic arts. It is the program that trained Neva Boyd’s most famous acolyte, Viola Spolin! Yes, that Viola Spolin: mother goddess of improvisational theatre, mother of Paul Sills, thus grandmother of Second City (Chicago), and godmother of The Groundlings (Los Angeles), ComedySporz (Los Angeles), Laughing Matters (Atlanta), Magnet Theatre (New York), Improv Asylum (Boston), ImprovBoston (Cambridge), Jet City Improv (Seattle), and improv companies in cities and towns all across America and the world. They all owe their origin to theatre games played in settlement houses.

the Recreational Training School there. The school taught a one-year educational program to teachers, in group games, gymnastics, dancing, play theory, social problems, and dramatic arts. It is the program that trained Neva Boyd’s most famous acolyte, Viola Spolin! Yes, that Viola Spolin: mother goddess of improvisational theatre, mother of Paul Sills, thus grandmother of Second City (Chicago), and godmother of The Groundlings (Los Angeles), ComedySporz (Los Angeles), Laughing Matters (Atlanta), Magnet Theatre (New York), Improv Asylum (Boston), ImprovBoston (Cambridge), Jet City Improv (Seattle), and improv companies in cities and towns all across America and the world. They all owe their origin to theatre games played in settlement houses.

Bravo New Jersey!!! They’ve accomplished something which, to our shame, we can only dream of in California: a return to arts education in EVERY SCHOOL IN THE STATE!

Bravo New Jersey!!! They’ve accomplished something which, to our shame, we can only dream of in California: a return to arts education in EVERY SCHOOL IN THE STATE! Cambique Tracey (

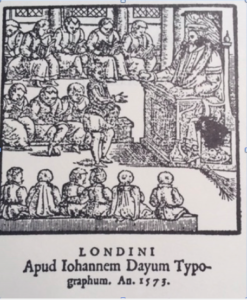

Cambique Tracey ( early 16th century England was a robust interest in pedagogy, with many books written on the subject. One of the most famous of those teacher/authors was Richard Mulcaster, who just happened to train Thomas Jenkins and John Cotham, two of Shakespeare’s teachers at Stratford’s Latin grammar school. Reading his two books, Positions and Elementarie, was one of the igniting revelations that got me going on my own book, because of Mulcaster’s use of the arts in his daily instruction. The title of my book is actually taken from a quote by a 17th century jurist who had been a student at the Merchant Taylors’ School while Mulcaster was the headmaster. He credited Mulcaster with offering daily instruction in both vocal and instrumental music, accompanied by dance, and with using theatre to teach “good behavior and audacity.” Mulcaster also included drawing as one of the essential teachings for young children, so all of the arts were present in his school.

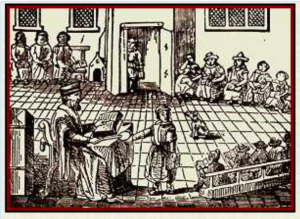

early 16th century England was a robust interest in pedagogy, with many books written on the subject. One of the most famous of those teacher/authors was Richard Mulcaster, who just happened to train Thomas Jenkins and John Cotham, two of Shakespeare’s teachers at Stratford’s Latin grammar school. Reading his two books, Positions and Elementarie, was one of the igniting revelations that got me going on my own book, because of Mulcaster’s use of the arts in his daily instruction. The title of my book is actually taken from a quote by a 17th century jurist who had been a student at the Merchant Taylors’ School while Mulcaster was the headmaster. He credited Mulcaster with offering daily instruction in both vocal and instrumental music, accompanied by dance, and with using theatre to teach “good behavior and audacity.” Mulcaster also included drawing as one of the essential teachings for young children, so all of the arts were present in his school. So now, my readers, I would like to engage you in the same visual exploration and see if we can draw some conclusions about Elizabethan classrooms.

So now, my readers, I would like to engage you in the same visual exploration and see if we can draw some conclusions about Elizabethan classrooms. Also, this last one is much busier than the others, and much more crowded (and there is no dog), so perhaps this one depicts a school in London?

Also, this last one is much busier than the others, and much more crowded (and there is no dog), so perhaps this one depicts a school in London? So far there are only a few of you that I know of who have delved into our largely unexplored history. Ultimately that history is what this site is all about. I love that people are reading my posts and I love the comments and the feedback. It feels like a community is building. But I’m greedy and I want more. I want others to join me in the research! Those of us who are advocates for more quality instruction in the arts for every student, every day, at every age NEED this history. Advocacy can take us only so far. We need to step back and take the long look, back to the ancients, when education began with the arts.

So far there are only a few of you that I know of who have delved into our largely unexplored history. Ultimately that history is what this site is all about. I love that people are reading my posts and I love the comments and the feedback. It feels like a community is building. But I’m greedy and I want more. I want others to join me in the research! Those of us who are advocates for more quality instruction in the arts for every student, every day, at every age NEED this history. Advocacy can take us only so far. We need to step back and take the long look, back to the ancients, when education began with the arts.