Boy Actors by John Lithgow

If you’ve been on the edge of your seat waiting for this final post on the boys’ companies active in the Tudor Age, you are probably alone, and I need to hear from you! This is a shame, because if theatre historians Harold Newcomb Hillebrand and Charles William Wallace are correct, the Globe Theatre and Shakespeare would never have happened without them!

My first three posts on this subject covered the immense popularity at court of the Children of St. Paul’s and the Children of the Chapel (along with many others that came and went and entertained the aristocracy in the provinces) up through the last decade of Elizabeth’s reign. The third post chronicled their demise as a result of politics and the far more active men’s companies. Hillebrand and Wallace wrote their books early in the last century, and since then there has been almost total silence. Fortunately their books are exhaustive in their detail, and if you can get your hands on them, you might join me in appreciating the role that boy actors played in our rich history

The truth is, the last gasp of the boys’ companies during the reign of James I, while dazzling and controversial, was brief; and it was entirely different from what had gone before. Both the Children of the Chapel and St. Paul’s had a second flowering with the ascendance of a new monarch, but their new life was a life sustained by a different breath—the breath of commerce. Ambitious entrepreneurs banked on the nostalgia for the playful antics of the boys who cavorted through the courts of Henry VIII and Elizabeth I, and they took a huge gamble. They had investors, and they threw their money around rashly, hiring the best playwrights available. Samuel Daniel, John Day, George Chapman, Thomas Middleton, John Marston, and Ben Johnson pocketed way more money writing for the boys than they did for the men, and their brilliant plays can still delight us; but the playful antics of the cavorting boy actors were not a good fit for them. Jacobean audiences had grown much more sophisticated, and they and demanded edgier and more dangerous fare than the children could manage.

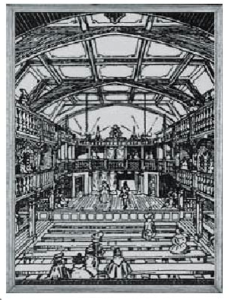

The exact dates aren’t available anymore, but by the end of 1600 both companies were up and running under new management. There was by this time a growing public passion for drama, and, remembering the hay-day of the Blackfriars, investors to believed they could turn a profit by re-opening it. James Burbage had purchased the property in 1596 to create an indoor home for his successful company, of which Shakespeare was a member. He had remodeled a section of it to build a handsome new theatre, but the neighbors had protested and prevented the opening of a public venue within the city limits. At some point, in order to defray the cost of keeping it open, he had leased it to what was essentially an incorporated body of profiteers, who used the old ruse of opening it as a “private” theatre to house the Children of the Chapel. As for the Children of Paul’s, the records are scant, but we do know that they were performing at St. Gregory’s Church with their new Master, Edward Pierce, dusting off old favorites and beginning to solicit new material.

Because there was no daily London Times archiving the doings of the city back then, most of our information about the boys’ companies from 1600 to 1616 comes from one of four sources: recorded performances at court; the licensing and publication of plays, in which there is usually a phrase telling where and by whom they were first performed; the written accounts of individual audience members; and law suits. Especially for the Children of the Chapel, the last source is perhaps the most fruitful, proving yet again that live theatre can be dangerous.

The first lawsuit of note came right away, in 1601, when Henry Clifton, Esq. sued Henry Evans, the new manager of Blackfriars, and Thomas Gyles, the Chapel master, essentially accusing them of kidnapping his son Thomas. The re-building of two new companies after a decade of silence had required aggressive recruitment tactics, and young Thomas had been recognized as a talent at his grammar school and had been impressed into service by the use of Gyles’ customary writ from the crown. The suit succeeded and young Thomas was released, but for our purposes, some interesting facts emerged from it. First of all, the suit gives us the names of a several boys who were impressed at that time and it makes it clear that the plaintiffs were guilty of over-stepping by capturing a boy from a family of substance—the son of a gentleman. Even more interesting: Clifton emphasized that the boys captured were “in no way able or fit for singing.” The purpose of the writ was, and had been for centuries, for the impressment of chapel boys to augment the choir, but these boys were not singers—they were actors! It wasn’t long before Gyles’ writ was re-written with clear wording stating that boys could not be impressed for the purpose of playing on the stage, “for that it is not fit or decent that such as should sing the praises of God almighty should be trained up or employed in such lascivious and profane exercises.”

Lascivious and profane or not, when James I became king, the boys’ companies were, at least for a while, well received. The Children of the Chapel were re-named the Children of the Queen’s Revels, and along with Paul’s boys there were two other minor companies formed, one for the Prince and one for the Princess.

Without going into fine detail, let us look at what distinguished these new boys’ companies from those that preceded them. From their inception, they were commercial ventures. Their material was not written by their choirmasters, or playwrights internally associated with them, but by hired, well-paid, professional dramatists. The boy actors did not exhibit the light, charming, playful style of their own: they were awkwardly, and often unsuccessfully, competing with and aping a new generation of brilliant adult thespians. Despite their princely names, these companies were ultimately not indebted to royal patronage: they were indebted to investors taking huge risks and hoping to reap huge profits. When these profits did not materialize, there were ugly, even violent, repercussions.

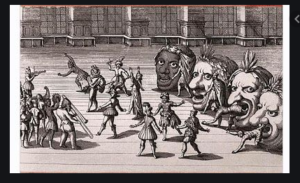

The boy actors had exited the Elizabethan era and entered the Jacobean, which for drama meant that the themes and topics that whetted the appetites of the audience were darker and more morally complex and ambiguous. Here is just a sampling of the titles that came from the pens of these titans to be performed by children at Blackfriars and St. Paul’s. I’ve seen and read only a few of these plays, but just the titles are enough to know that they were acerbic and witty in tone, and they trespassed on forbidden ground. Chapman wrote Bussy D’Ambois, The Gentleman Usher, May Day, Monsieur d’Olive, and The Widow’s Tears. Middleton wrote A Mad World My Masters, A Trick to Catch the Old One, and Your Five Gallants. Marston wrote Parasitaster, The Malcontent, and The Dutch Courtesan, which was honored by being performed at court for the King of Denmark’s visit. Ben Jonson wrote Cynthia’s Revels, The Poetaster, and Epicoene, or the Silent Woman, which was the most famous comedy of its time (which I can easily believe because I had to giggle just reading the synopsis). He also collaborated with Chapman and Marston on the ill-fated Eastward Ho, as we shall see.

All of these were excellent plays and enjoyed success, but they must have been a stretch for boy actors. They were filtered through a new aesthetic. Audiences had changed. Educated by Shakespeare and his peers, these audiences were as brilliant as the plays they were observing. They were not satisfied with the old song and dance and delight of the masques. They wanted intellectual spice and a touch of danger, and the great playwrights knew how to give it to them.

There is one other expert source of information about those years. In Hamlet, Shakespeare tells us much about the children of Blackfriars and Paul’s. In this exchange between Rosencrantz and Hamlet, Rosencrantz reports from the city and explains why the traveling theatre company visiting Elsinore is on the road and not performing at home:

Hamlet: How chances it they travel? Their residence, both in reputation and profit, was better both ways.

Rosencrantz: I think their inhibition comes by the means of the late innovation.

Hamlet: Do they hold the same estimation they did when I was in the city? are they so followed?

Rosencrantz: No, indeed, are they not.

Hamlet: How comes it? Do they grow rusty?

Rosencrantz: Nay, their endeavour keeps in the wonted pace: but there is, sir, an aery of children, little eyases, that cry out on the top of question, and are most tyrannically clapped for’t: these are now the fashion, and so berattle the common stages–so they call them–that many wearing rapiers are afraid of goose-quills and dare scarce come thither.

Hamlet: What, are they children? Who maintains ’em? How are they escorted? Will they pursue the quality no longer than they can sing? Will they not say afterwards, if they should grow themselves to common players—as it is most like, if their means are no better—their writers do them wrong, to make them exclaim against their own succession?

Rosencrantz: ‘Faith, there has been much to do on both sides; and the nation holds it no sin to tar them to controversy: there was, for a while, no money bid for argument, unless the poet and the player went to cuffs in the question.

Hamlet: Is’t possible?

Guildenstern: O, there has been much throwing about of brains.

Hamlet: Do the boys carry it away?

Rosencrantz: Ay, that they do, my lord; Hercules and his load too.

For the modern reader, just to make it easy, I’ll highlight and translate the salient points made here. Hamlet [Shakespeare] is concerned that the reputation and profit of the men’s companies are suffering because of the boy actors, whom he characterizes as squawking little eyases [eaglets]. He also demonstrates a very real concern for the boys themselves—I would guess because the abuse of the writ for impressment of choirboys, for acting instead of singing, meant that there was no provision made by the crown to send them to university. They were being poorly housed and once their voices broke they would have no choice but to grow into “common players” (a reflection of his opinion of his own profession?). He refers to a battle being waged between playwrights and adult players over payment for the best scripts, implying that the boys’ companies could pay more and get better material, and he infers that the boys are winning the battle.

He further notes that “the nation holds it no sin to tar them to controversy,” meaning that the public is not offended by seeing children dabble in political mockery. Their plays are so satirical and topical that people of influence—those “wearing rapiers”—are afraid to attend for fear of being mocked by the playwrights, those with “goose-quills.” (Here he seems to be acknowledging the ever-true maxim that the pen is mightier than the sword.)

That was roughly 1603. Very soon there were other battles being fought in the courts and in taverns, with opponents occasionally even coming to blows. The profits that had been promised the naive investors in Blackfriars were nowhere near the reality, and endless legal squabbles were inevitable. Hillebrand tries to untangle a mare’s nest of suits that went on for years and cost the Children of the Revels dearly. The eventual results of most of the suits were lost in the warehouses of paper records that had not yet been examined when Hillebrand wrote his book, and, indeed, may still lie neglected somewhere. But they don’t matter here. The trail of suits, even without than their closure, gives us a vivid glimpse into the times for our boys

It was the daring characteristic of the boys (or, in truth, their playwrights) to “cry out at the top of the question” that did them in at the end. Four plays in particular “berattled” the stage, although there were certainly others.

In 1604 the Children of the Queens Revels performed Samuel Daniel’s Philotas, which closely paralleled the career of the popular Earl of Essex, only recently hanged for treason. That play was banned for seeming to meddle in the affairs of the state, and Samuel Daniel was called to account for it, but he managed to talk his way our of trouble by convincing the judges that he had started it long before Essex’s rebellion.

Then early in 1605 they performed Eastward Ho, the play mentioned above, by Jonson, Chapman, and Marston. That play mocked the Scotsmen who surrounded the Scottish King James and were much disliked by the old guard. Chapman and Jonson spent some time cooling their heels in prison for that one, but Marston, who was probably the one most responsible, got away. More significantly, the boys lost their connection to the Queen and were henceforth simply called the Children of the Revels. The Queen apparently wanted nothing more to do with them and had her title removed.

Jonson and Chapman were pardoned and released after some chastened pleading, but apparently they hadn’t learned their lesson, The very next year Jonson collaborated with John Day on The Isle of Gulls, in which two characters titled “Duke” and “Duchess” were thinly veiled caricatures of James I and Queen Anne. It portrayed the court as a bawdy house of crooks, where bribes were taken for favors and advancements. This was indeed an impudent over-stepping of the boundaries: clearly the potential for profit outweighed the danger.

Nathan Field, who began his illustrious career as an child actor with the Children of the Chapel

Somehow the boy players had thus far survived, either because the courts were not paying close attention or because some liberality was still extended due to their youth. Boy actors enjoyed the same kind of tolerance as jesters at court, able to speak veiled truth as jokes, without giving offence. But then came the last straw: Chapman’s The Conspiracy and Tragedy of Charles, Duke of Biron. In this play the King and his Scottish favorites were again targeted, and the King was portrayed as a drunkard, striking gentlemen and cursing the heavens over a hawking mishap. This time the King had had enough, and he closed all the theatres in London. Blackfriars remained closed for a long time, and when it re-opened it was not for boys—it was for Burbage’s company, now called the King’s Men.

In hindsight, it is hard to imagine how the boys’ companies got away with their daring for as long as they did and why they kept it up despite censure. Here again, I suspect that part of the reason was commercial. There is a necessary element of risk present in all successful theatre that pushes the boundaries and asks an audience to examine its beliefs and values, and one must again remember that the Jacobean audience was voracious. They had come to expect, even demand, a healthy touch of risk in their entertainment. The child actors couldn’t act with the same subtlety and skill that the audience had come to expect from the men’s companies, so in order to draw crowds they had to specialize in what had worked for them so well in the past—which was satire—and they had to do it in excess.

When the end came the King’s harshness was certainly intensified by his reaction to the Gunpowder Plot. It was in 1605 that a group of Catholic conspirators came within a hair’s breadth of changing the course of history by blowing up the entire court and most of the aristocracy of England. It didn’t happen, and today it is mostly remembered by the bonfires and fireworks that make up the gleeful celebration of Guy Fawkes Day; but the danger was very real. James Shapiro’s recent book The Year of Lear describes wonderfully how the exposure of the plot turned the King into a paranoiac and his court into a bastion. What he tolerated before November 5, 1605, he could never tolerate again.

In 1609 Burbage took back the lease at Blackfriars, which had been closed for several months, and at the same time he paid off Edward Pierce, then the choirmaster at St. Paul’s, to stop performing. The Children of the Revels and the Children of St. Paul’s were finished. Some of the boys were re-constituted briefly in yet another abandoned monastery, called the Whitefriars, as a short-lived company called the King’s Revels, and they limped along for a few years performing minor works by minor playwrights, but by 1616 that ended as well. For several years thereafter there were traveling companies of boys, claiming to be the Revels, but they were strictly provincial and only a wisp of smoke from the ashes of their glory days.

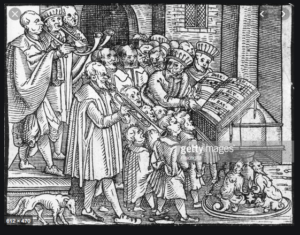

“No one knows when boy singers were added to the Chapel Royal or other church choirs, but they were probably present from the very beginning, their treble voices being thought to be the closest to the voices of angels. There was a religious pursuit of this purity of tone. Churches, abbeys and cathedrals were designed acoustically to capture it: massive sound boxes that amplified these “fairest voices.” Choir schools, attached to churches and training children for church choirs, played a role in the pre-reformation history of British education. They offered free education to able students. Their purpose was to assure a sufficient number of well-trained voices to supply the needs of the church. As we shall see, Erasmus himself attended a song school in Utrecht, perhaps because it was an opportunity for a free education. The earliest choirmasters were usually almoners, the men who distributed alms to the needy.

“No one knows when boy singers were added to the Chapel Royal or other church choirs, but they were probably present from the very beginning, their treble voices being thought to be the closest to the voices of angels. There was a religious pursuit of this purity of tone. Churches, abbeys and cathedrals were designed acoustically to capture it: massive sound boxes that amplified these “fairest voices.” Choir schools, attached to churches and training children for church choirs, played a role in the pre-reformation history of British education. They offered free education to able students. Their purpose was to assure a sufficient number of well-trained voices to supply the needs of the church. As we shall see, Erasmus himself attended a song school in Utrecht, perhaps because it was an opportunity for a free education. The earliest choirmasters were usually almoners, the men who distributed alms to the needy. into service for the crown, and the Chapel Royal consistently had a small number of singers to complement the adult musicians. Their voices were, and are to this day, a thing of transcendent beauty. Boys’ voices broke later five hundred years ago than they do today, evidently because there was less protein in the diet. A boy who began his service in the Chapel at the age of seven or eight could continue to sing sweetly until the age of sixteen or seventeen, during which time he received an education overseen by the choirmaster.

into service for the crown, and the Chapel Royal consistently had a small number of singers to complement the adult musicians. Their voices were, and are to this day, a thing of transcendent beauty. Boys’ voices broke later five hundred years ago than they do today, evidently because there was less protein in the diet. A boy who began his service in the Chapel at the age of seven or eight could continue to sing sweetly until the age of sixteen or seventeen, during which time he received an education overseen by the choirmaster.