Cleveland Settlement House Memory Project

A few years before my parents died, we were visiting New York City and they took me on a little tour of their early lives as young marrieds in Greenwich Village. Back then, in the mid-30s, my dad was starting his career as an actor with the Federal Theatre Project. They lived on Commerce Street, a short block from the Cherry Lane Theatre.

Anyone who has lost  both parents is haunted by the lost opportunity to ask unanswered questions. I’m no different. Now that I am pursuing this history project I could kick myself for not filling in the snippets of information they shared casually over the years. That day, walking around the Village, we passed the Greenwich House, a settlement house founded in 1902, and my mom just tossed out this tidbit: “I taught creative dramatics there.” How had I missed that fact—that before I was born, my mom did a stint doing exactly what I ended up doing as a career, and I never knew it!? What was it like for her back then?

both parents is haunted by the lost opportunity to ask unanswered questions. I’m no different. Now that I am pursuing this history project I could kick myself for not filling in the snippets of information they shared casually over the years. That day, walking around the Village, we passed the Greenwich House, a settlement house founded in 1902, and my mom just tossed out this tidbit: “I taught creative dramatics there.” How had I missed that fact—that before I was born, my mom did a stint doing exactly what I ended up doing as a career, and I never knew it!? What was it like for her back then?

So I started searching the internet and found an article written in 1986 by Margaret E. Berry, Former Executive Director of the National Federation of Settlements and Neighborhood Centers. There I was astonished to learn how many progressive movements that we now take for granted had their roots in the settlement houses: The kindergarten (child garden) movement, federal fair housing legislation, legal aid services, meals on wheels for the elderly, even Roosevelt’s New Deal and the Works Projects Administration! But what struck me most were the philosophical underpinnings of their arts and cultural activities programs.

So I started searching the internet and found an article written in 1986 by Margaret E. Berry, Former Executive Director of the National Federation of Settlements and Neighborhood Centers. There I was astonished to learn how many progressive movements that we now take for granted had their roots in the settlement houses: The kindergarten (child garden) movement, federal fair housing legislation, legal aid services, meals on wheels for the elderly, even Roosevelt’s New Deal and the Works Projects Administration! But what struck me most were the philosophical underpinnings of their arts and cultural activities programs.

Young artists at Hull House

The Settlement Movement began in the late 19th century as a social experiment, to address the cultural needs of impoverished communities. It was modeled after Toynbee Hall, established in London in 1884 “as a practical tool for remedying the cruelty, exploitation, and bleakness found in city life.” The first settlement house in the United States was University Settlement in New York City, but the most famous was Hull House, established by Jane Addams in Chicago. Eventually there were over 400 settlement houses in cities and towns across the country.

Here’s an interesting fact: the reason they were called “settlement houses” is because a variety of caring groups “settled in” to neighborhoods with wretched living conditions, to learn as well as to help. They lived in the communities and shared the stresses endemic to neighborhoods of poverty. They did not approach their jobs as teachers, but as students: students of the huge diversity of cultures pouring into our nation at the time.

Music lesson at a Philadelphia settlement house

Social dance class at The Memory Project in a Cleveland settlement house

My best source so far, in searching for the answers to questions I never got to ask my mother, is a monograph written in 2011 by Nick Rabkin: “Teaching Artists and the Future of Education.” In it he makes the assertion that, “Artists have worked in community-based arts education for more than a century, and the roots of their work in schools are found in arts programs at the settlement houses at the turn of the last century.” To quote Margaret Berry, “In the settlement house there were always activities which brought fun and fulfillment to life—music, art, theater, sociability and play.” But Rabkin points out that the settlement houses cast out the old conservatory model of arts training in favor of a much more socially conscious, all inclusive model, in which art making and art exploration was “for everyone and essential to the fabric of a democratic society.” The iconic example is that instead of art students standing in smocks at easels, painting vases, a drawing lesson at Hull House might be a class of scruffy youngsters sketching the unsanitary conditions in the alley behind the settlement. Teachers at the settlement houses taught aesthetics and technical skills but were also “attentive to the arts as tools for critical exploration of the world, celebration of community values and traditions, weaving the arts into daily life, cultivation of imagination and creativity, and appreciation of the world’s many cultures.” We see in this philosophy the derivation of the strands of our national instructional standards in the arts.

Hull House is where the great swing era clarinetist, Benny Goodman, learned music, and the Home for Colored Waifs in New Orleans gave us Louis Armstrong. Social dance, modern dance, and creative movement were regular offerings, as were culturally embedded crafts.

Neva Boyd

And then there was Neva Boyd, who taught at Hull House and then founded  the Recreational Training School there. The school taught a one-year educational program to teachers, in group games, gymnastics, dancing, play theory, social problems, and dramatic arts. It is the program that trained Neva Boyd’s most famous acolyte, Viola Spolin! Yes, that Viola Spolin: mother goddess of improvisational theatre, mother of Paul Sills, thus grandmother of Second City (Chicago), and godmother of The Groundlings (Los Angeles), ComedySporz (Los Angeles), Laughing Matters (Atlanta), Magnet Theatre (New York), Improv Asylum (Boston), ImprovBoston (Cambridge), Jet City Improv (Seattle), and improv companies in cities and towns all across America and the world. They all owe their origin to theatre games played in settlement houses.

the Recreational Training School there. The school taught a one-year educational program to teachers, in group games, gymnastics, dancing, play theory, social problems, and dramatic arts. It is the program that trained Neva Boyd’s most famous acolyte, Viola Spolin! Yes, that Viola Spolin: mother goddess of improvisational theatre, mother of Paul Sills, thus grandmother of Second City (Chicago), and godmother of The Groundlings (Los Angeles), ComedySporz (Los Angeles), Laughing Matters (Atlanta), Magnet Theatre (New York), Improv Asylum (Boston), ImprovBoston (Cambridge), Jet City Improv (Seattle), and improv companies in cities and towns all across America and the world. They all owe their origin to theatre games played in settlement houses.

Improvisation games are now included in actor training, and they bring joy and laughter to theatre education programs in schools and community programs. K-12 school teachers with some improv training use theatre games to illuminate text and subtext in stories from literature and history and across the curriculum. Neva Boyd’s training program also very possibly trained the teaching artist who trained my mom to teach creative dramatics in the late 30s at Greenwich House.

Bravo New Jersey!!! They’ve accomplished something which, to our shame, we can only dream of in California: a return to arts education in EVERY SCHOOL IN THE STATE!

Bravo New Jersey!!! They’ve accomplished something which, to our shame, we can only dream of in California: a return to arts education in EVERY SCHOOL IN THE STATE! Cambique Tracey (

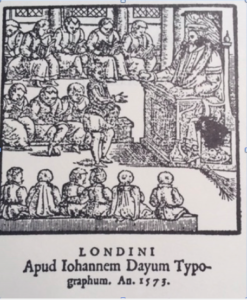

Cambique Tracey ( early 16th century England was a robust interest in pedagogy, with many books written on the subject. One of the most famous of those teacher/authors was Richard Mulcaster, who just happened to train Thomas Jenkins and John Cotham, two of Shakespeare’s teachers at Stratford’s Latin grammar school. Reading his two books, Positions and Elementarie, was one of the igniting revelations that got me going on my own book, because of Mulcaster’s use of the arts in his daily instruction. The title of my book is actually taken from a quote by a 17th century jurist who had been a student at the Merchant Taylors’ School while Mulcaster was the headmaster. He credited Mulcaster with offering daily instruction in both vocal and instrumental music, accompanied by dance, and with using theatre to teach “good behavior and audacity.” Mulcaster also included drawing as one of the essential teachings for young children, so all of the arts were present in his school.

early 16th century England was a robust interest in pedagogy, with many books written on the subject. One of the most famous of those teacher/authors was Richard Mulcaster, who just happened to train Thomas Jenkins and John Cotham, two of Shakespeare’s teachers at Stratford’s Latin grammar school. Reading his two books, Positions and Elementarie, was one of the igniting revelations that got me going on my own book, because of Mulcaster’s use of the arts in his daily instruction. The title of my book is actually taken from a quote by a 17th century jurist who had been a student at the Merchant Taylors’ School while Mulcaster was the headmaster. He credited Mulcaster with offering daily instruction in both vocal and instrumental music, accompanied by dance, and with using theatre to teach “good behavior and audacity.” Mulcaster also included drawing as one of the essential teachings for young children, so all of the arts were present in his school. So now, my readers, I would like to engage you in the same visual exploration and see if we can draw some conclusions about Elizabethan classrooms.

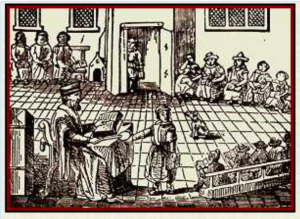

So now, my readers, I would like to engage you in the same visual exploration and see if we can draw some conclusions about Elizabethan classrooms. Also, this last one is much busier than the others, and much more crowded (and there is no dog), so perhaps this one depicts a school in London?

Also, this last one is much busier than the others, and much more crowded (and there is no dog), so perhaps this one depicts a school in London?