My grand and ambitious purpose in writing this book was to change the focus of education from “for the benefit of test scores” to “for the benefit of the commonwealth,” and to make it stick by promoting joy.

My grand and ambitious purpose in writing this book was to change the focus of education from “for the benefit of test scores” to “for the benefit of the commonwealth,” and to make it stick by promoting joy.

To quote from the conclusion:

My plea to everyone concerned about the physical and emotional health of young people in this post-pandemic, digital age (and I hope that is everyone) is to make room for joy in our schools. Not just joy in play: joy in learning. My greatest hope as an educator is that the era of drill, kill, test, and repeat will end. If you think “kill” is too strong a word in the context of educating children, consider that one can kill enthusiasm. One can kill exploration, motivation, and joy. The testing industry has made a fortune off or our innocent kids. It’s time for a re-examination of the purposes and parameters of standardized testing, opting instead for authentic assessment that is supportive of growth.

The jabs of my small spear in this effort are just barely beginning to be felt by the policy makers, but you, my readers, can help by spreading the word.

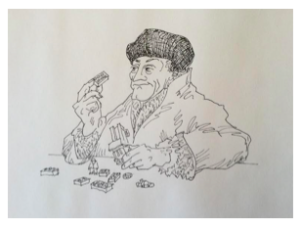

Last week Susan Cambigue Tracey, of the Music Center’s Education Division, generously hosted my first reading, and we had great fun featuring performances of some of Erasmus’ hilarious colloquies. Colloquies were short scripted playlets used in schools to teach the important art of conversational (as opposed to classical) Latin. Both classical and conversational (colloquial) were taught intentionally in the Latin grammar schools that Shakespeare and thousands of his peers attended. Latin was the lingua franca of businessmen, clergymen, lawyers, ambassadors, and other travelers on the continent In the 16th century. Travelers had to be able to chat, joke, and negotiate with their peers all over Europe. Classical Latin was for the university. Colloquial Latin was for business.

And colloquial Latin was very much in Erasmus’ realm. Talk about joy in learning! Erasmus invented it!

If you think about your school years, all of the most memorable learning moments were probably accompanied by either pain or joy. My aim is to diminish the power of pain in learning and elevate the power of laugher and joy. I stand with Erasmus on that.