This from the Washington Post yesterday: Leading public education advocates write open letter to Joe Biden: Your ‘statements encourage us’

This from the Washington Post yesterday: Leading public education advocates write open letter to Joe Biden: Your ‘statements encourage us’

If Biden stands by what Diane Ravitch quotes him as saying in her letter, every public educator needs to get out and work for his election.

When “The Death and the Life of the Great American School System” was published in 2009 I devoured it in one sitting. It was a palpable relief to have such a credible authority give voice to the frustrations of an entire generation of veteran educators. I found an email address for Diane Ravitch at NYU and sent her a thank you, and, remarkably, she responded. Since then, with “Reign of Error,” published a few years later, and her daily blogs posted relentlessly over the past decade, I have watched her almost single handedly succeed in what ten years ago seemed impossible: pushing back against the tide of the delusional reform ideas funded by corporate privatizers. For that she joins my short list of truly courageous heroes.

A half century ago, after my first disastrous and ego-shattering semester teaching first graders, with an emergency credential that required no training, and having no legitimacy besides what was (at least in that situation) a worthless BA from an ivy league school, I fled to San Francisco. It was the summer of love and I just desperately needed to dance in the streets with the hippies. One evening I found myself sitting with friends in a coffee shop, in a booth next to a group of policemen. Their caps were hanging from the rack above me and I could see little John Birch Society pins stuck into the inner rims. I had heard of the Birch Society and had a vague idea that it was a megaphone for the right-wing, but I had never actually spoken to a member or paid any attention to their doctrine.

When the policemen left, they left a booklet on the table. Out of curiosity I took it home and read it. I was astounded. The first page, the first chapter, in fact the entire booklet was about doing away with public education. The arguments had the resonance of outrage: “Why should people with no children pay taxes to pay for other people’s children to be educated?” “If people want children they should pay for their education themselves!” “Parents of children in private schools should not have to pay for education the children of the poor,” etc.

At the time I just wrote it off as crazy talk. What about the bedrock of democracy? What about the benefit to the commonwealth? What about humanism, the Renaissance, the Reformation, the Enlightenment? Did these guys actually want to throw us back into the middle ages? I wrote it off as the work of lunatics and tossed the booklet in the garbage.

How I wish I had kept it!

Within a year I had entered the Los Angeles school district’s new intern program and began training and teaching with support and guidance. I got a job at a school with an exuberant principal named Kathy Henry, who would come into my chaotic classroom and shout over the noise, “Oh, you lucky children! Your teacher is so creative!!” and I would think, what???? I’m dying here! But I didn’t die, I got better and over the years I think I became a pretty good teacher, at least some of the time. (And don’t let anyone tell you great teachers are great all the time and were born that way.) Kathy Henry gave me the courage to stay in a profession I grew to love, and I will always be grateful.

But I was in the classroom and then in administration for long enough to see wave after wave of educational “reform” sweep through. I sat through one in-service after another, and countless men and women in suits sold us products and programs designed to improve our practice. I and most of my experienced colleagues just watched each wave go by, taking the good parts and discarding the rest with an “uh huh, been there, done that” attitude. But I couldn’t help watching the upheavals they caused through the lens of that booklet. I was too busy teaching and raising my own kids to dig deeper into what was happening around me. I had never heard of the Koch brothers (whose father was a founder of the Birch Society) or the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), which was busy pushing bill after bill through legislative pipelines designed to undermine the work we teachers were patiently and expertly doing in our classrooms.

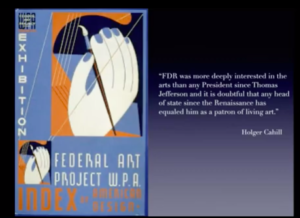

When I started teaching, most every school in Los Angeles had a full-time music teacher and a full-time visual arts teacher. My second graders had a music class and a visual arts class every week. To finish my credential I had to take two classes in teaching the arts: one in music and one chosen from dance, theater, or visual arts. That was 1970. Within ten years that was ancient history. Within another twenty years I had started teaching high school English and Drama, and the entire focus of education had shifted to “accountability” e.g. test scores. We teachers were expected to teach to the test, the arts were seen as extra curricular electives, not core, and the crucial role of the arts in education had become a footnote.

So when Diane Ravitch came along and explained clearly and brilliantly exactly why and how this travesty had happened, starting with the free market champion Milton Friedman in the 50s, everything became clear. Why had I not seen it?

Initially, at the administrative level in the district, “The Death and the Life of the Great American School System” was well received in LAUSD. Our instructional leadership welcomed it. I remember that Jim Morris, who was the fine head of instruction at the time, purchased copies for every one of the administrators reporting to him. But Morris soon moved on and was replaced by leaders who bowed to the pervasive pressure (and the money behind it), and for a painful era test scores ruled.

And then there came the charters and yet another flood of money. After I retired I worked on the agonizing campaign to re-elect our visionary board president, Steve Zimmer, and watched as the charter schools association poured over twelve million dollars into the coffers of his opponent: a young man in his early thirties who never attended public schools himself but had one disillusioning year teaching with Teach for America in one of the district’s most challenging middle schools. They won. Zimmer was defeated, and we lost a true champion for our students. It was the same year Trump was elected and I think I was more horrified by Zimmer’s loss than Clinton’s, only because I watched it happen from the inside—watched their strategy—watched them field four opponents in the general election to drain away just enough votes to force a runoff, and then flood the field with expensive, negative, and dishonest ads targeting Westside voters. Very few voters come out for a runoff elections, and they must have spent hundreds of dollars per vote to pull of that scam.

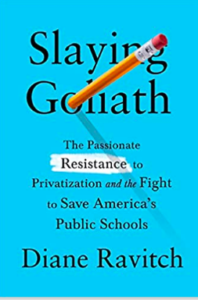

But now I think that was the nadir, and Ravitch’s new book, “Slaying Goliath,” is full of examples of hope. Here in Los Angeles and across the country, new public school advocates are being elected to school boards, teachers unions are making a powerful resurgence. When our schools finally reopen and, we have new leadership at the national level, I hope we will see a flood of new and better policies, and the arts will be back in full.

Fingers crossed!

The Los Angeles County School For the Arts is honoring me and my brother, John Lithgow, with the

The Los Angeles County School For the Arts is honoring me and my brother, John Lithgow, with the  Kate Zoeger is loving my book! Here’s what she has to say:

Kate Zoeger is loving my book! Here’s what she has to say:

Dear readers, do any of you believe that that the January 6th rioters were made up of citizens who had had a rich education in the arts? I don’t. The arts humanize us. They teach us empathy. I believe that if the arts were deeply embedded in K-12 education throughout our nation, those riots would never have happened and our states would be vastly more healthy and united.

Dear readers, do any of you believe that that the January 6th rioters were made up of citizens who had had a rich education in the arts? I don’t. The arts humanize us. They teach us empathy. I believe that if the arts were deeply embedded in K-12 education throughout our nation, those riots would never have happened and our states would be vastly more healthy and united.

This from the Washington Post yesterday:

This from the Washington Post yesterday:  I’ve just finished a riveting memoir titled What You Have Heard is True, by Carolyn Forché. It is about the lead-up to the civil war in El Salvador in the 80s. I recommend it highly because of the perspective Forché gives on our troubling history with Central America and our current concern for immigrants and separated families at the border.

I’ve just finished a riveting memoir titled What You Have Heard is True, by Carolyn Forché. It is about the lead-up to the civil war in El Salvador in the 80s. I recommend it highly because of the perspective Forché gives on our troubling history with Central America and our current concern for immigrants and separated families at the border. Reading this I remembered that I’ve heard this twice before. Barbara Kingsolver said the

Reading this I remembered that I’ve heard this twice before. Barbara Kingsolver said the  exact same thing about her book The Lacuna, which tells the story of Tolstoy’s time living in Mexico. In The White Goddess, Robert Graves describes a time in ancient British history when poets sat next to kings in government. Poets are, and have always been, valued in other cultures far more than they are in ours. They interpret, clarify, and vivify the times to which they are witness.

exact same thing about her book The Lacuna, which tells the story of Tolstoy’s time living in Mexico. In The White Goddess, Robert Graves describes a time in ancient British history when poets sat next to kings in government. Poets are, and have always been, valued in other cultures far more than they are in ours. They interpret, clarify, and vivify the times to which they are witness.