So far there are only a few of you that I know of who have delved into our largely unexplored history. Ultimately that history is what this site is all about. I love that people are reading my posts and I love the comments and the feedback. It feels like a community is building. But I’m greedy and I want more. I want others to join me in the research! Those of us who are advocates for more quality instruction in the arts for every student, every day, at every age NEED this history. Advocacy can take us only so far. We need to step back and take the long look, back to the ancients, when education began with the arts.

So far there are only a few of you that I know of who have delved into our largely unexplored history. Ultimately that history is what this site is all about. I love that people are reading my posts and I love the comments and the feedback. It feels like a community is building. But I’m greedy and I want more. I want others to join me in the research! Those of us who are advocates for more quality instruction in the arts for every student, every day, at every age NEED this history. Advocacy can take us only so far. We need to step back and take the long look, back to the ancients, when education began with the arts.

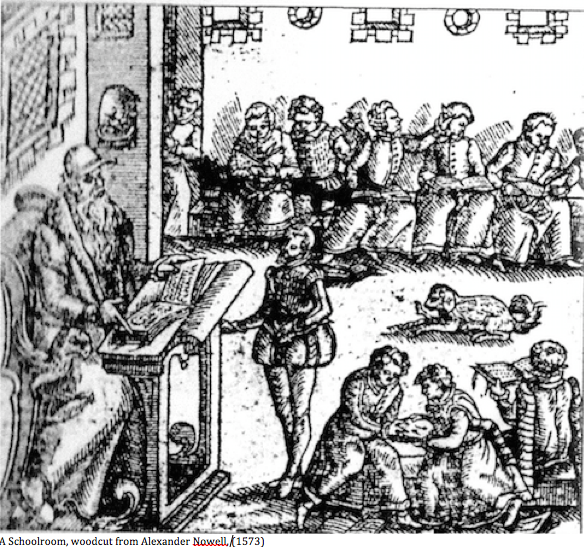

Just to clarify: theatre incorporates all of the arts. When Shakespeare was in school, during the heyday of the humanist education designed by Erasmus, theatre was not considered an arts discipline distinct from its components: artful language, dramatic acting, dance, music, and visual spectacle. Theatre then was like film is today. It embraced all of the arts. Just look at today’s categories for the Oscars: best score, best song, best costumes, best special effects, best script, and dance numbers highlighting everything. Only a small minority of the awards are for acting or directing. Theatre, historically was the same. When we are looking at the history of theatre education, we are looking at the history of all of arts education.

This is still a new site with a small but growing number of followers, and so far it hasn’t gained much traction in its main purpose, but I am ever hopeful. The field so far is barren, especially for dance and theatre. Music in education has

Drama Class

ancient roots, all the way back to the Quadrivium, where it shared equal status with arithmetic, geometry, and astronomy. As for visual arts: there are entire Arts History Departments in every university that document the history of conservatory training. Dance was usually taught in partnership with music. But nothing like that exists for the long history of theatre in education. Unless I am mistaken (and I’ve searched and searched) this rich story remains largely undocumented.

My upcoming book, Good Behavior and Audacity: Humanist Education, Playacting, and a Generation of Genius, is a small step taken to help fill the void. It looks at one moment at the turn of the 17th century where there is substantial evidence of a lively presence in schools of music and dance, physical rhetoric or “actio” applied to memorization of the classics, boys’ theatre companies at court, school performances to entertain villagers, and the use of dramatic colloquies in the teaching of conversational Latin. It is obviously a part of a profound tradition, but perhaps because it was always taken for granted and not part of the formal curriculum, historians haven’t woven together the threads.

Right now I’m focusing my own exploration on the 20th century and will be posting soon about arts education in Settlement Houses and the Federal Theatre Project. Some other areas I’m hoping to pursue myself or welcome others to explore:

The Greeks: Epicurus (the Garden), Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, Demosthenes

The Romans: Lucretius, Cicero, Quintilian

The Humanists: Dante, Vittorino da Fletre (La Giocosa – “The Pleasure House”), Guarino da Verona, Aeneas Sylvius, Sturmius, Bembo, Erasmus, Guido Camillo (Theatre/Memory), Ascham, Vives, Mulcaster, Elyot, Montaigne, Comenius

19th Century: Sloyd, the Kindergarten (“child garden”) Movement, Horace Mann

20th Century: John Dewey (note guest post by Dain Olsen), Settlement Houses, Federal Theatre Project

If you have any information about any of the above or have other topics to explore, pitch in! This is the place!