This is fun!

In The Taming of the Shrew, before the shrew, Kate, matches wits with Petruchio in their hilarious first encounter, the illiterate servant Grumio warns her that Petruchio will “disfigure” her with his “rope-tricks.” He’s referring to Petruchio’s scathing facility with rhetoric (which Grumio hears as rope-tricks) and his ability to use rhetorical “figures” to counter and obliterate any argument she might throw at him.

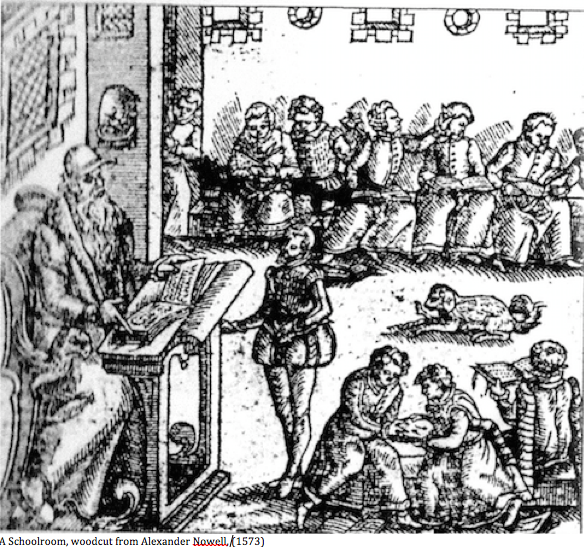

A schoolroom, woodcut from Alexander Nowell (1573)

When Shakespeare was a student, only a few generations after the printing press had been invented, rhetoric had been at the core of a child’s education for over two thousand years. Before literacy was prevalent, the ability to persuade though speech gave enormous power to the “rhetor,” the public speaker. The ability to make language punch and pop, to make the listener sit up and pay attention (or else!), was considered the most important skill of a person educated in the liberal arts. All through ancient times, the middle ages, and well into the Enlightenment, the “Trivium” (grammar, logic, and rhetoric) were the foundational subjects taught first to a child in elementary, or “trivial” school.

Shakespeare had to be able to recognize and practice in his speaking and in his writing at least 132 rhetorical figures, tropes, and devices. He had to be able to practice expressive, physical rhetoric (or rhetorical dance) every time he stood on his two feet and spoke to his teachers or his classmates. “Per Quam Figuram?” was the question asked repeatedly, all day, every day: “What figure are you using?”

Here are a couple of passages from my book to illustrate:

* * *

Today a well-educated person might be able to list about twenty-five figures that are still commonly used. Examples would be alliteration, allusion, amplification, analogy, antithesis, apostrophe, assonance, climax, dilemma, epithet, hyperbole, irony, metaphor, metonymy, onomatopoeia, paradox, parenthesis, personification, simile, and synecdoche. But there were dozens more that Shakespeare had to learn. How about:

Epizeuxis: Howl, howl, howl, howl, howl! (Lear)

or

Never, never, never, never, never (Lear)

or

O wonderful, wonderful, wonderful, and yet again wonderful (Celia)

Catachresis: I will speak daggers to her (Hamlet)

Anadiplosis: My conscience hath a thousand several tongues, / And every tongue brings in a several tale, / And every tale condemns me for a villain (Richard III)

Hyperbaton: Some rise by sin, and some by virtue fall (Escalus)

Hendiadys: to have the due and forfeit of my bond (Shylock)

* * *

When Brutus or Macbeth meditates on the murderous crime he is anticipating, he is exhibiting examples of aporia: doubting or questioning one’s motives.

When Antony repeats again and again “Brutus is an honorable man,” or Othello keeps interrupting Desdemona with his demand for “the handkerchief,” or Hotspur repeatedly squawks “Mortimer” like a parrot, they are all using the figure epimone: the repetition of the same point in the same words.

Whereas when Othello is about to suffocate Desdemona with a pillow and says, “Put out the light, and then put out the light,” he is using diacope: using the same phrase twice, but with two different meanings.

When Brutus asks the Roman mob, “Whom have I offended?” he is using anacoenosis: calling upon the counsel of an audience.

When the grave digger in Hamlet argues that if a man goes to water and drowns it is suicide, but if the water comes to him and drowns him he is “not guilty of his own death,” he is using cacosistation: an argument that serves both sides.

When Cesario asks Feste if he lives by his tabor (e.g. is he a drummer?) and Feste responds, “No, sir, I live by the church,” we call that antanaclasis: two contrasting meanings for the same word, causing ambiguity.

When Macbeth contemplates the assassination of Duncan and considers that it will “catch/With his surcease, success,” he is using paronomasia: the intentional use of two words with similar sounds but different meanings, to exploit confusion.

When Mercutio has been fatally stabbed and he responds to his friends’ questions about his wound, “Ay, ay, a scratch, a scratch,” the figure he is using is meiosis: a deliberate understatement.

When Prince Hal distracts the sheriff from his attempt to arrest Falstaff, he his using apoplanesis: evasion by digression to a different matter. Then again, when Falstaff pretends to be deaf when the Justice of the Peace wants to question him about a robbery, and babbles on, consoling the Justice about his own maladies, he is using concessio: where a speaker grants a point which hurts the adversary to whom it is granted. When he debates with himself about the virtues of honor and concludes that it is a “mere scutcheon, therefore I’ll have none of it,” he is using hypophora: reasoning with one’s self by asking questions and answering them.

The examples are endless. All the folded language, all the layering and amplifying of extended metaphors, all the colorful and unexpected uses of words, all can be traced back to rhetorical figures. Once you start to learn them you see them everywhere, and as you get better at it, reading a passage in one of the plays can be enormous fun, like deciphering an intricately clever puzzle. But, oh, there are so many!

* * *

We’ve had some great orators, and some of the figures they’ve used have become cultural memes—think of Kennedy’s “Ask not what your country can do for you; ask what you can do for your country” (chiasmus)—but those examples stand out as exceptional. In Shakespeare’s day, every educated person had that power. Anyone who could not “hold court” on cue, could not stand in front of an audience and hold them spellbound, was pretty much irrelevant.

Just try to imagine, dear reader, the mental flexibility required of a child of ten or eleven, every day having to invent phrases based on the models above. No wonder they were so smart!

Fascinating!

Sent from my iPhone

>

terrific job……keep up the good work

Wonderful work! That is the type of info that are supposed to be

shared around the net. Shame on the seek engines for

not positioning this post higher! Come on over and seek advice

from my web site . Thank you =) and i working for thue may chu

Thank you!

At this time I am going to do my breakfast, later than having my breakfast coming over again to read further news.|

I truly appreciate this post. I¦ve been looking all over for this! Thank goodness I found it on Bing. You’ve made my day! Thanks again

Just desire to say your article is as amazing.

The clarity in your post is just great and i could assume you are an expert on this subject.

Fine with your permission let me to grab your feed to keep up to

date with forthcoming post. Thanks a million and please keep up the

rewarding work. and i working for thue may chu ao

The rhetorical devices are fascinating. What a richness of language they produce. . . hence Shakespeare! Wow, yes, what an amazing thing for youngsters to be practicing every day. And I’m sure they could do it. The book is a delight. Your writing so entertaining and fluid. Can’t wait for it to be published!