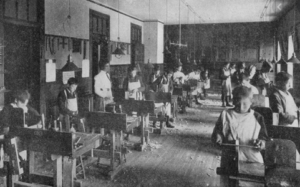

A Sloyd Woodworking Class

When I was in elementary school a zillion years ago, we had wood shop for one afternoon every week. ALL afternoon. An old garage on the campus was fitted out as a complete workshop, with big wooden tables and all the tools and lumber we needed. I made a boat, a book shelf, and a soapbox car for our soapbox derby. I also carved a wooden spoon that my mom used in the kitchen for the rest of her life. Entire classes at the school took on projects like building playground equipment and lunch tables and a covered wagon. I learned how to use a ruler, a tape measure, a compass and protractor, and I learned all the mathematics of measurement. I learned to use hand tools: the saws, the drills, the vise, the rasp, and the sander. I learned that you have to see a project through to the end and not do a slapdash job of it. Pretty good lessons!

Children working at sloyd benches

My school, Antioch Elementary, in Yellow Springs, Ohio, still exists. It was founded in 1923 on the educational theories being developed at the time by the education philosopher John Dewey, and today it is the longest uninterrupted Dewey-based school in America. I had always thought that the educational justification for such a luxurious use of my school time was Dewey’s philosophy of learning by doing. I had absolutely no idea that it was based on a nineteenth century pedagogy from Finland.

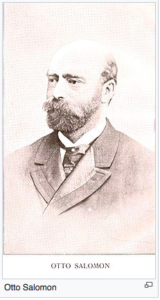

Once when I was in the Los Angeles Unified School District’s Arts Education Branch, our staff took a little field trip to the LAUSD archives to visit our curator. She was preparing a trunk of artifacts to take around to schools as a local history lesson. One of the items was a second grade report card from the year 1900 on which there were  grades for five subjects: reading, writing, arithmetic, music, and sloyd. We were baffled. What the heck was “sloyd,” and why was it so important that it actually had to be graded?! Back then iPhones were brand new and only one person present had one. He whipped it out and within seconds we learned that sloyd means “handicrafts,” and it was a Finnish pedagogy started by Uno Cygnaeus in Finland in 1865 and refined by the Swedish educator Otto Salomon (who, like Richard Mulcaster, who trained Shakespeare’s teachers in the 16th century, worried about the fact that elementary school is too boring for children, and solved the problem by giving them something to DO!). The system was further refined and promoted worldwide, and was introduced in the United States in the 1890s by Meri Toppelius. It is still taught as a compulsory subject in Finland, Denmark, Sweden, and

grades for five subjects: reading, writing, arithmetic, music, and sloyd. We were baffled. What the heck was “sloyd,” and why was it so important that it actually had to be graded?! Back then iPhones were brand new and only one person present had one. He whipped it out and within seconds we learned that sloyd means “handicrafts,” and it was a Finnish pedagogy started by Uno Cygnaeus in Finland in 1865 and refined by the Swedish educator Otto Salomon (who, like Richard Mulcaster, who trained Shakespeare’s teachers in the 16th century, worried about the fact that elementary school is too boring for children, and solved the problem by giving them something to DO!). The system was further refined and promoted worldwide, and was introduced in the United States in the 1890s by Meri Toppelius. It is still taught as a compulsory subject in Finland, Denmark, Sweden, and  Norway. One of my theatre teachers is married to a man from Finland, and she tells me that he still proudly displays embroidery he did in his sloyd class in school when he was a child.

Norway. One of my theatre teachers is married to a man from Finland, and she tells me that he still proudly displays embroidery he did in his sloyd class in school when he was a child.

The Antioch School is affiliated with the college, and my peers there, in the 50s, were mostly the children of professors—a fairly rarified community. Dewey’s educational philosophy was certainly studied and admired back then: it influenced education in public schools but was never fully implemented. After Sputnik and A Nation at Risk it fell out of favor almost completely and we seldom hear of it now. But sloyd pre-dated Dewey, and there in the archives of the Los Angeles schools was rock solid evidence that the project-based learning Dewey promoted was alive and well and mandatory at the turn of the century, in at least one major school district in the United States, a generation before Dewey began writing about education.

It turns out it was more than just Los Angeles. Toppelius and her sister Sigrid were invited first to Boston, where they set up training programs. Sigrid stayed in Boston while Meri went on to Chicago where she started a sloyd

It turns out it was more than just Los Angeles. Toppelius and her sister Sigrid were invited first to Boston, where they set up training programs. Sigrid stayed in Boston while Meri went on to Chicago where she started a sloyd  department in Chicago’s Agassiz school. They also trained teachers as in Bay View Michigan as part of a Chautauqua summer program. So by the end of the century, at least three major cities in the United States were employing sloyd in at least some of their schools, and there were major training programs in sloyd attracting teachers and administrators from across the country. (I’ll keep researching this. If any of my readers know anything more about it, please share!)

department in Chicago’s Agassiz school. They also trained teachers as in Bay View Michigan as part of a Chautauqua summer program. So by the end of the century, at least three major cities in the United States were employing sloyd in at least some of their schools, and there were major training programs in sloyd attracting teachers and administrators from across the country. (I’ll keep researching this. If any of my readers know anything more about it, please share!)

If you’re interested in learning more about sloyd, here is link to a PBS program called “Who Wrote the Book of Sloyd” that’s pretty entertaining. It features the very old book on the left, which was re-issued in 2013: “The Teacher’s Hand-Book of Slöjd” by Otto Salomon. Sloyd is really about all of the handicrafts, including sewing, weaving, knitting, crochet, embroidery, and paper folding, all of which we learned at the Antioch School, but its most lasting impact on education in the United States was on programs that included woodworking.

John Dewey was certainly influenced by the sloyd movement, as he was by the Settlement movement I have written about in a previous post. It has always struck me how completely the arguments for arts education align with the philosophy of Dewey and of sloyd. Engaged learning. Productive learning. Project-based learning. Hands-on learning. They’re all related and they all lead to deep and enduring learning. They all incorporate the body and the mind into the cognitive process. I didn’t know at the time how incredibly lucky I was to be educated in that way, but I loved school, and for all of my years as a teacher and arts administrator I have endeavored to give my students something of the joy I experienced as a child in the wood shop.

Bravo New Jersey!!! They’ve accomplished something which, to our shame, we can only dream of in California: a return to arts education in EVERY SCHOOL IN THE STATE!

Bravo New Jersey!!! They’ve accomplished something which, to our shame, we can only dream of in California: a return to arts education in EVERY SCHOOL IN THE STATE! So far there are only a few of you that I know of who have delved into our largely unexplored history. Ultimately that history is what this site is all about. I love that people are reading my posts and I love the comments and the feedback. It feels like a community is building. But I’m greedy and I want more. I want others to join me in the research! Those of us who are advocates for more quality instruction in the arts for every student, every day, at every age NEED this history. Advocacy can take us only so far. We need to step back and take the long look, back to the ancients, when education began with the arts.

So far there are only a few of you that I know of who have delved into our largely unexplored history. Ultimately that history is what this site is all about. I love that people are reading my posts and I love the comments and the feedback. It feels like a community is building. But I’m greedy and I want more. I want others to join me in the research! Those of us who are advocates for more quality instruction in the arts for every student, every day, at every age NEED this history. Advocacy can take us only so far. We need to step back and take the long look, back to the ancients, when education began with the arts.